Abstract

Transcatheter aortic valve implantation (TAVI) is a less invasive alternative to surgical aortic valve replacement (SAVR) for patients with symptomatic severe aortic stenosis (AS) and a high operative risk. Risk stratification plays a decisive role in the optimal selection of therapeutic strategies for AS patients. The accuracy of contemporary surgical risk algorithms for AS patients has spurred considerable debate especially in the higher risk patient population. Future trials will explore TAVI in patients at intermediate operative risk. During the design of the SURgical replacement and Transcatheter Aortic Valve Implantation (SURTAVI) trial, a novel concept of risk stratification was proposed based upon age in combination with a fixed number of predefined risk factors, which are relatively prevalent, easy to capture and with a reasonable impact on operative mortality. Retrospective application of this algorithm to a contemporary academic practice dealing with clinically significant AS patients allocates about one-fourth of these patients as being at intermediate operative risk. Further testing is required for validation of this new paradigm in risk stratification. Finally, the Heart Team, consisting of at least an interventional cardiologist and cardiothoracic surgeon, should have the decisive role in determining whether a patient could be treated with TAVI or SAVR.

Introduction

Transcatheter aortic valve implantation (TAVI) is rapidly emerging as a viable and less invasive alternative to surgical aortic valve replacement (SAVR) for high-risk patients with symptomatic severe aortic valve stenosis (AS)1-4. In spite of the ever improving outcome with SAVR, especially in higher risk cohorts, the EURO Heart survey suggested that a considerable number of AS patients are denied surgery for various reasons including age, left ventricular (LV) dysfunction and comorbidities5. By precluding sternotomy and cardiopulmonary bypass, TAVI provides the potential for off-pump and beating heart valve implantation, which may translate into faster recovery, shorter hospitalisation and more rapid improvement in quality of life. Risk stratification plays a decisive role in the optimal selection of therapeutic strategies among AS patients.

Various national and multicentre TAVI registries, and single centre experiences have reported favourable short- and mid-term clinical outcomes1-4,6,7. Cohort B of the randomised Placement of Aortic Transcatheter Valves (PARTNER) trial demonstrated an important improvement in 1-year mortality and quality of life with TAVI as compared to optimal medical therapy and/or isolated balloon aortic valvuloplasty in prohibitive surgical risk patients8. The PARTNER Cohort A demonstrated similar 1-year survival rates among high-risk patients randomly assigned to either TAVI or SAVR. Vascular complications and neurological events, however, were higher in the TAVI cohort, whereas atrial fibrillation and major bleeding were more frequent in the SAVR cohort9. From a European perspective, the PARTNER trial has to be critically commented on in regard to the fact that a) patients were selected, thus not all-comers were treated and, b) patients were on a waiting list, both of which may lead to improved outcomes.

The applicability of contemporary surgical risk algorithms for AS patients has spurred considerable debate in both cardiac surgery and cardiology communities10-14. The STS Predicted Risk of Mortality (PROM) and the logistic EuroSCORE have been widely applied to determine the operative mortality risk of AS patients undergoing SAVR. Both scoring models, however, are fraught with shortcomings, especially in higher-risk patient populations currently undergoing TAVI. These risk models in isolation may not provide a satisfactory risk assessment. Even though the combination of different risk scores may improve their predictive value, combining risk models to determine a predictive value has not been validated and raises practical concerns. It is axiomatic that a risk-scoring model should be relatively simple, reliable and reproducible.

The SURgical replacement and Transcatheter Aortic Valve Implantation (SURTAVI) trial is a multicentre randomised trial to assess the optimal treatment strategy for patients with symptomatic, severe AS at intermediate risk by randomising patients to either SAVR or TAVI with the Medtronic CoreValve System™ (Medtronic, Minneapolis, MN, USA).

Our aim was to illustrate the process of conceptualising a randomised trial with TAVI and SAVR in patients with symptomatic severe AS at intermediate operative risk with respect to the current knowledge of risk stratification. We briefly underscore the inconsistencies and shortcomings of the two widely used risk models (STS PROM and Logistic EuroSCORE). In accordance with the body of contemporary published literature, we suggest that the concept of risk stratification could be based upon age in combination with a fixed number of predefined risk factors. It should be emphasised that, in all scenarios, the Heart Team, consisting of at least an interventional cardiologist and cardiothoracic surgeon, has a decisive role in determining whether a patient could be treated with TAVI or SAVR15.

Inconsistencies in the Logistic EuroSCORE and STS PROM

Models for predicting surgical outcomes on the basis of preoperative patient characteristics are valuable tools for research, quality improvement and clinical practice and may even be used for patient counselling about an individual’s operative risk.

The STS PROM and Logistic EuroSCORE are widely used risk models to assess the operative risk of AS patients16-19. However, inaccurate risk estimation for surgical AVR is more the rule than the exception, and inconsiderate use of these algorithms for benchmark performance testing could lead to inappropriate enthusiasm for technologic innovations like TAVI10,13. Recent data suggest that a risk model containing only three variables (age, EF and creatinine) might have at least as good accuracy and calibration as the more complex risk models20. An Italian multicentre study analysing 29,659 consecutive patients who underwent cardiac surgery demonstrated that this same simple model led to overestimation of short-term operative mortality risk in patients at very-low risk and, conversely, underestimation in patients at very-high risk21.

Rationale for the algorithm of 10 risk factors

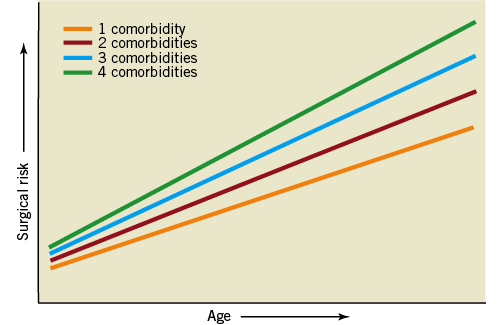

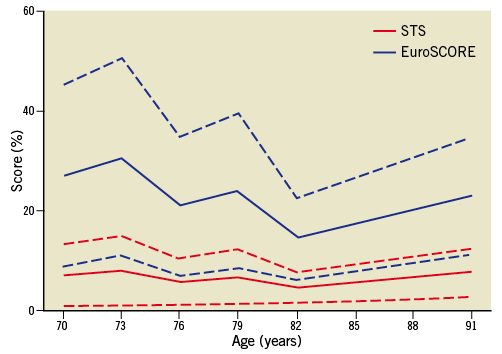

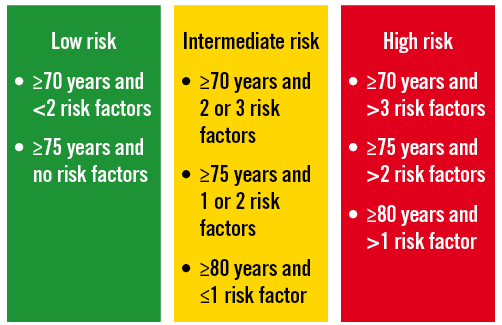

With the established shortcomings of currently used risk models in mind we moved to a novel concept of risk stratification, the so-called SURTAVI model. Clearly, according to established risk models like the STS PROM and Logistic EuroSCORE, an increasing number of risk factors will augment an individual patient’s risk. This begs the question of whether a patient’s operative risk will be based on age and the number of risk factors present (Figure 1). Analysis of the impact of different risk variables and their combination in different age cohorts in the STS score and Logistic EuroSCORE suggests risk variables can accommodate for age resulting in similar overall risk profiles. An arbitrarily defined intermediate risk with STS score <10 and/or Logistic EuroSCORE <20 is reached by either the combination of an age of 70-74 years with two or three comorbidities, or an age of 75-79 with one or two comorbidities or an age ≥80 and one or no comorbidities (Figure 2). The SURTAVI model 1) emphasises the pivotal importance of the independent “age” variable and 2) allows the identification of an intermediate risk group across different age cohorts based on the number of predefined risk variables. A younger patient with more risk factors may have a similar risk profile as that of an older patient who has less risk factors. Accordingly, the SURTAVI algorithm defines a low-risk, intermediate and high-risk cohort (Figure 3).

Figure 1. Concept of risk models: impact of age and comorbidities on operative risk.

Figure 2. Intermediate risk in the SURTAVI model (combination of age 70-74 years and two or three comorbidities, age 75-79 and one or two comorbidities and age ≥80 and one or no comorbidities) and resultant STS and Logistic EuroSCORE.

Figure 3. Principles of the SURTAVI model.

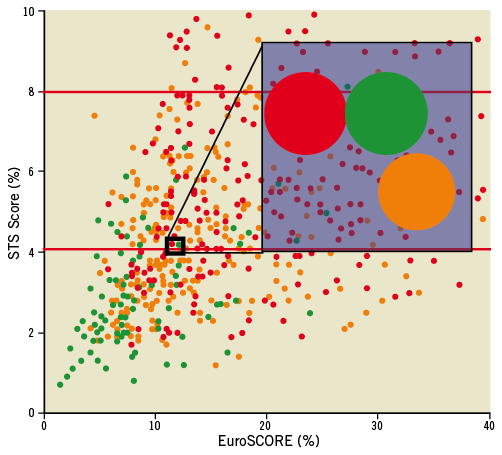

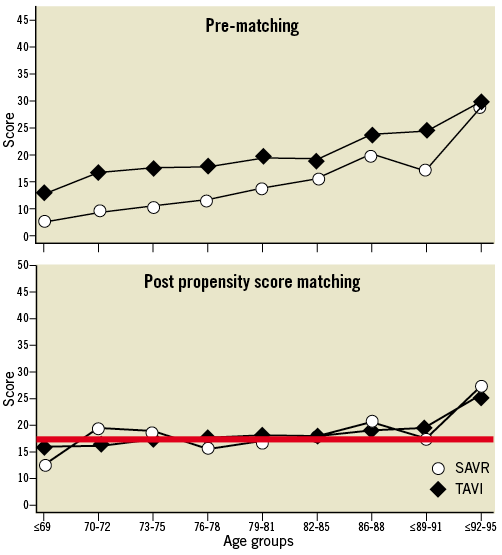

Data from the Bern-Munich-Rotterdam (BERMUDA) initiative illustrated the concept of age and comorbidities in a pooled dataset of 2,884 SAVR and 782 TAVI patients. The estimated logistic EuroSCORE increased with age, while each age group of TAVI patients had a higher logistic EuroSCORE than SAVR patients (Figure 4). Propensity score matching analysis identified a patient cohort of 784 patients (392 in each group) and demonstrated 1) both TAVI and SAVR cohorts had similar estimated operative risks according to the Logistic EuroSCORE and 2) the risk profile was similar across all age groups (Figure 4). The latter illustrates that younger patients had more comorbidities than their older counterparts, which therefore counterbalanced the risk related to age in this study. Figure 5 demonstrates that neither the STS score nor Logistic EuroSCORE can uniformly discriminate between a patient’s operative risk. An STS score of 4 for instance did not correlate with a logistic EuroSCORE nor with the proposed SURTAVI model. Apparently, the established risk models do not uniformly determine a patient’s operative risk.

Figure 5. The dots represent the STS and EuroSCORE of each individual patient in the propensity matched database from the BERMUDA initiative (see text). The colour code refers to the risk classification according to the SURTAVI model. Green: low risk; orange: intermediate risk; red: high risk. The shaded area magnifies three patients with an STS score of 4% and a Logistic EuroSCORE of 10%. According to the SURTAVI model this combination could result in low-, intermediate- or high-risk.

Figure 4. BERMUDA initiative. Upper Panel: Logistic EuroSCORE in different age groups for TAVI and SAVR. Lower Panel: Propensity score matched (PSM) analysis: constant Logistic EuroSCORE across age groups suggesting more comorbidities in lower age groups.

RISK FACTOR SELECTION PROCESS

The risk algorithm should be applicable to potential TAVI candidates. Therefore, particular variables that would preclude TAVI are excluded (e.g., infectious endocarditis, concomitant valve surgery, emergent procedure, multivessel or left main stem coronary artery disease with a SYNTAX score >33, etc… see Appendix). Selected risk factors should be relatively prevalent, easy to capture and have a reasonable impact on operative mortality.

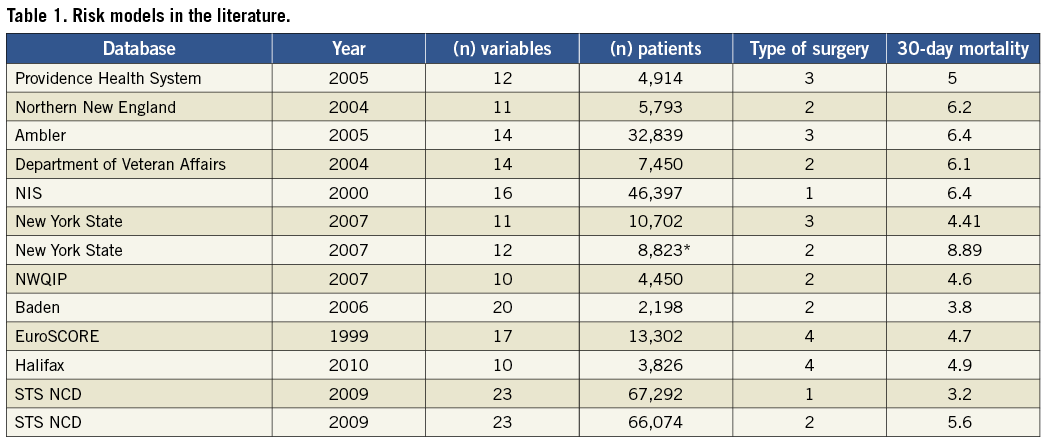

We reviewed the risk models evaluated in the last 15 years and ranked the contained variables according to their corresponding odds ratio in the respective risk models14,16,17,19,22-31 (Table 1, Figure 6). Apart from age, cardiac reoperation, depressed LV function; chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), renal insufficiency, cerebrovascular disease, peripheral arterial disease, pulmonary hypertension and diabetes emerged. Particular variables not listed in previous models appear relevant in a higher risk population eligible for TAVI, and would therefore merit consideration. Previous mediastinal radiation, liver failure, chest deformity, porcelain aorta and frailty were evaluated32-37. It is especially frailty that has emerged as a significant and prevalent risk factor for operative mortality. Depending on the definition used, its prevalence in an AS population would vary from 4 to 50%36-38.

Figure 6. Odds ratio of variables in different surgical risk models.

Eventually, ten risk factors were selected.

Each variable was defined according to contemporary literature and those used by professional societies/organisations:

1. SIGNIFICANT CONCURRENT CORONARY ARTERY DISEASE (CAD) REQUIRING REVASCULARISATION

Multivessel CAD and/or left main stem disease with a calculated SYNTAX score >33 make catheter bound therapies less favourable, and would be considered a relative contraindication for TAVI. Previous CABG or PCI is not considered to have considerable impact on short-term outcome.

2. FRAILTY

In the absence of a generally accepted consensus definition, frailty is defined as suggested by Lee and co-workers by the presence of any one of the following36: 1. Katz score (independence in “activities of daily living”); 2. Ambulation (walking aid/assist?); 3. Diagnosis of (pre)dementia.

3. LEFT VENTRICULAR DYSFUNCTION

Defined as an EF <35%, with respect to the pivotal position of this particular threshold in the heart failure population39.

4. NEUROLOGICAL DYSFUNCTION

Neurologic disease severely affecting ambulation or day-to-day functioning excluding TIA and carotid artery disease, adapted from the Logistic EuroSCORE19.

5. PULMONARY DISEASE

COPD Gold Stage II: moderate COPD with worsening airflow limitation (FEV1/FVC <70%; 50% ≥FEV1 <80% predicted), with shortness of breath typically developing on exertion40.

6. PERIPHERAL VASCULAR DISEASE

Adapted from the STS risk model: claudication, either with exertion or at rest; amputation for arterial vascular insufficiency; vascular reconstruction, bypass surgery, or percutaneous intervention to the extremities; documented aortic aneurysm with or without repair; positive noninvasive test (e.g., ankle brachial index ≤0.9, ultrasound, magnetic resonance or computed tomography imaging of >50% diameter stenosis in any peripheral artery, i.e., renal, subclavian, femoral, iliac); noninvasive carotid test with >60% diameter occlusion or prior carotid surgery or symptomatic carotid stenosis >50%16,41-43.

7. RENAL DISEASE

At least moderate chronic kidney disease with GFR <60 mL/min according to the National Kidney Foundation kidney disease outcome quality initiative advisory board44.

8. REDO CARDIAC SURGERY

9. PULMONARY HYPERTENSION

>60 mmHg at most recent measurement.

10. DIABETES MELLITUS

On oral or insulin therapy.

An expert panel of interventional cardiologists and cardiac surgeons assessed and confirmed the selected variables and introduced the feature of the “open box” in order to capture those risk variables that would appear less prevalent, but nevertheless would merit consideration for the risk stratification of the individual AS patient. Typical entities in the “open box’ will be (among others) porcelain aorta, complex chest deformity, previous extensive mediastinal radiation and advanced liver failure (Child-Pugh class C).

Application of the SURTAVI model in practice

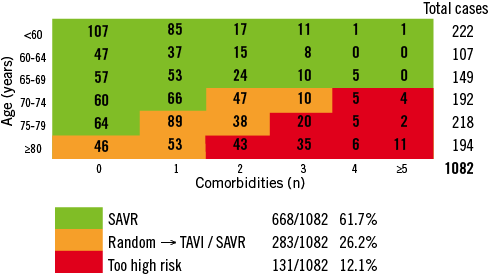

As proof of concept, we applied the SURTAVI risk algorithm to all AS patients undergoing SAVR or TAVI over a 5-year period in the Thoraxcenter, Rotterdam, The Netherlands. Data collection was complete for the TAVI cohort, whereas frailty was not reliably monitored in the SAVR cohort. Figure 7 illustrates the subdivision of patients into three risk groups according to the SURTAVI algorithm. Over 60% of cases would be deemed low risk, whereas 26% would be adjudicated at intermediate risk. This implies that the anticipated SURTAVI trial entails grossly one fourth of contemporary AS practice.

Figure 7. Rotterdam database on AS patient undergoing SAVR or TAVI and categorisation into three risk groups according to the SURTAVI model.

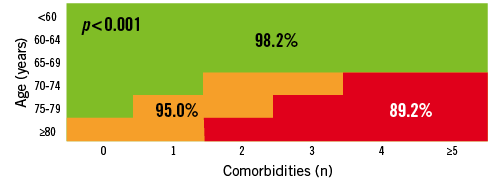

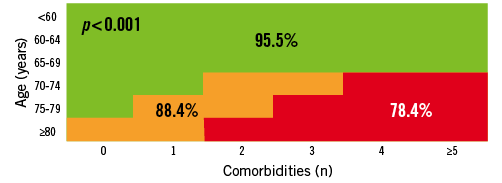

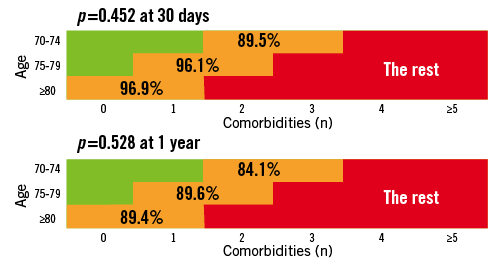

The incomplete data on frailty and the “open box” items (porcelain aorta, liver failure, mediastinal radiation…) suggest that patients could shift to a higher risk cohort based on the presence of additional risk variables not captured in the predefined “list of 10 comorbidities” or frailty. With these limitations in mind, the 30-day mortality was 98.2, 95.0 and 89.2% (p <0.001) and the 1-year mortality was 95.5, 88.4 and 78.4% (p <0.001) in the low, intermediate and high-risk groups respectively (Figure 8 and Figure 9). As for the intermediate risk group in particular, we could not detect any difference in outcome between the three age cohorts underscoring the SURTAVI concept of risk stratification (Figure 10).

Figure 8. Rotterdam database on AS patient undergoing SAVR or TAVI: 30-day mortality in low-, intermediate- and high-risk cohorts.

Figure 9. Rotterdam database on AS patient undergoing SAVR or TAVI: 1-year mortality in low-, intermediate- and high-risk cohorts.

Figure 10. Rotterdam database on AS patient undergoing SAVR or TAVI: 30-day and 1-year mortality in the intermediate risk cohort according to different age groups.

FDA perspective

Initially started as an investigator driven trial, SURTAVI evolved into a so-called industry sponsored (i.e., Medtronic Inc.) trial seeking Investigational Device Exemption (IDE) approval by the Federal Drug Administration (FDA). Since TAVI heralds the use of a “significant risk device”, FDA approval is essential to qualify for future regulatory purposes and product labelling in the USA. Therefore, a complete pre-IDE application was submitted to the FDA for critical review. According to the FDA, the STS Risk Calculator should be used for mortality prediction with outliers allowed by qualitative surgical assessment for patients with risk factors not captured by the STS score. A calculated risk between 4 and 8% would define intermediate risk. The FDA argued against the introduction of arbitrary age-range groups. Furthermore, the FDA suggested many of the comorbidities could be interpreted as representing minimal risk. Finally, the FDA also stated that less prevalent risk factors to be captured in the “open box” (like porcelain aorta, immunosuppressive disorders, mediastinal radiation…) would place a patient immediately in the high-risk category. Although the protocol has been revised according to the FDA suggestions, we still believe the above-stipulated SURTAVI risk paradigm is valid, and indeed may prove to be an accurate and yet user-friendlier tool, in identifying the “intermediate risk” patient.

Conclusion

The forthcoming SURTAVI trial introduces a new concept of risk stratifying patients with severe AS undergoing surgical or catheter based therapy. Risk stratification is based on the combination of age and a fixed number of predefined risk variables. Retrospective application of this algorithm to a contemporary academic practice dealing with clinically significant severe AS patients allocates about one fourth of patients as being at intermediate operative risk, which will constitute the target patient population for the SURTAVI trial. Further testing is required for validation of this new paradigm in risk stratification.

Conflict of interest statement

G.van Es is an employee of Cardialysis BV. All other authors have no conflict of interests to declare.

Appendix

– Exclusion criteria for SURTAVI model

– Blood dyscrasias as defined: leukopenia (WBC <1000 mm3), thrombocytopenia (platelet count <50,000 cells/mm3), history of bleeding diathesis or coagulopathy, or hypercoagulable states

– Ongoing sepsis, including active endocarditis

– Cardiogenic shock manifested by low cardiac output, vasopressor dependence, or mechanical haemodynamic support

– Recent (within six months of randomisation) cerebrovascular accident (CVA) or transient ischaemic attack (TIA)

– Gastrointestinal (GI) bleeding within the past three months

– Severe dementia (resulting in either inability to provide informed consent for the trial/procedure, prevents independent lifestyle outside of a chronic care facility, or will fundamentally complicate rehabilitation from the procedure or compliance with follow-up visits)

– Multivessel coronary artery disease with a SYNTAX score >33

– Estimated life expectancy of less than 12 months due to associated non-cardiac comorbid conditions

– Evidence of an acute myocardial infarction ≤30 days before the index procedure

– Need for emergency surgery for any reason

– End stage renal disease requiring chronic dialysis or creatinine clearance <20 cc/min