Abstract

Aims: Stent thrombosis (ST) is an infrequent but potentially fatal complication of PCI. The reported incidence of ST varies from 0-5%, due to differences in definition of ST, inclusion/exclusion criteria, and the type of stent and dual antiplatelet therapy used. We aimed to examine the incidence of ST and associated risk factors in this “real-world, all-comers” study.

Methods and results: All patients undergoing PCI at South Yorkshire Cardiothoracic Centre (UK) between 2007 and 2010 were included, with no exclusion criteria. ST cases were divided into definite and probable ST, according to the ARC criteria. Univariate predictors were identified using Student’s t-test and chi-square test, and entered into a Cox proportional hazards model to identify factors independently associated with ST. For 5,833 PCI patients followed up for two years, the incidence of definite and probable ST together was 1.9% (n=109); of these 73% were early, 11% late and 16% very late ST. Cardiogenic shock, ST-elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI), lack of dual antiplatelet treatment, diabetes mellitus, stent length and stent diameter were the independent predictors of ST.

Conclusions: The incidence of definite/probable ST in this “real-world” registry is 1.9%. Cardiogenic shock, often excluded in clinical trials, is the strongest independent predictor of ST.

Introduction

Stent thrombosis (ST) after percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) is an infrequent but potentially fatal complication1. The rate of ST in the published literature varies from under 1% to over 5%2-7. Even in studies with newer-generation drug-eluting stents, the ST rate varies significantly from one study to another7,8. This variation depends upon multiple factors including the definition of ST, the types of stent used, the study era, the type and duration of antiplatelet therapy, the proportion of stable vs. acute patients, and variation in risk factor profile and clinical practice of different geographical regions. The risk factors for ST can be divided into patient-related and procedure-related factors9. Patient-related factors include: discontinuation of antiplatelet therapy5,10,11; lack of response to antiplatelet therapy12; diabetes mellitus13-15; renal dysfunction13,14; and acute coronary syndromes (ACS)14,16. Procedure-related factors include: procedural complications (e.g., coronary artery dissection)5,17; inadequate stent deployment or sizing10,16; and choice of stent, i.e., bare metal stents (BMS) or drug-eluting stents (DES)1,10,18.

The clinical trials tend to present ST rates for a particular type of stent used in a selected patient cohort, whereas the registry data can evaluate the ST rates in a real-life experience in a certain geographical area. There is a need for contemporary registries to examine incidence and risk of ST continuously. We aimed to examine the incidence and risk factors leading to ST in this “real-world, all-comers” study.

Methods

STUDY POPULATION

This was a retrospective analysis of prospectively collected data from consecutive patients undergoing PCI with stent deployment at the South Yorkshire regional cardiothoracic centre between 2007 and 2010. This centre is the only one providing a PCI service to the population in and around Sheffield, 1.8 million people in total. It incorporates a PCI service for all indications, including stable symptoms, ACS, and primary PCI for ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI). The PCI procedure and adjunctive pharmacotherapy were at the discretion of the operator, but adhered to relevant local, national and international guidelines. Of particular note, dual antiplatelet therapy (DAPT) for 12 months for all ACS patients and all patients receiving a DES was the default approach. For elective patients receiving a BMS, DAPT was suggested for a minimum of one month. However, since this was an all-comers study, some patients had single-agent therapy due to side effects, contraindications or comorbidities. Intraprocedural heparin, and not bivalirudin, was the default anticoagulation therapy, along with selective use of a glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitor, where indicated. There were no exclusion criteria.

DATA COLLECTION

All patients who underwent PCI in the specified timeframe were identified using our electronic database. Demographic, clinical and angiographic data were collected from hospital records. Renal failure was defined as creatinine level of >200 µmol/L, chronic heart failure (CHF) as symptomatic heart failure with ejection fraction less than 30%, and cardiogenic shock as systolic blood pressure <100 mmHg along with signs or symptoms of hypoperfusion.

The Academic Research Consortium (ARC) definitions of ST were used in this study. ARC divides ST into three categories: definite ST, defined as angiographically or pathologically confirmed ST with acute ischaemic symptoms or ECG changes or rise in cardiac biomarkers; probable ST, defined as any unexplained death within 30 days of PCI or any myocardial infarction (MI) related to acute ischaemia in the territory of the implanted stent without angiographic confirmation of stent thrombosis and in the absence of any other obvious cause; and possible ST defined as any unexplained death beyond 30 days19. Although we identified the cases of possible ST occurring within a year of the index procedure, we have used only definite/probable ST to identify risk factors of ST. We also categorised ST into ARC defined timescales: early, occurring within 30 days; late, between 30 and 365 days; and very late, after 365 days.

Outcome data were collected using the national mortality database, hospital electronic database and patient records. All events were adjudicated by three cardiologists independently and, in cases of difference of opinion, by a consensus view or the majority vote.

DATA ANALYSIS

Data are presented as mean±SD or as percentages (proportions) unless otherwise stated. Analysis was carried out using Student’s t-test or one-way ANOVA for continuous variables and chi-square or Fisher’s exact test for categorical variables. Variables with significant trend (p≤0.1) were entered into a Cox proportional hazards model to identify factors independently associated with ST. All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS version 21 (IBM, Armonk, NY, USA).

Results

PATIENT CHARACTERISTICS

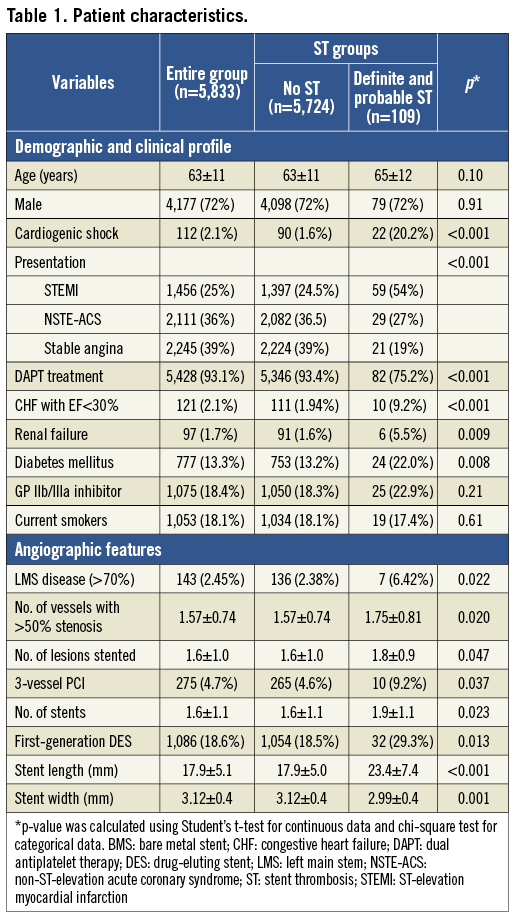

During the study period, 5,833 patients underwent PCI with stent implantation. The mean age was 63±11 years; 72% of the patients were male, 13% were diabetic. Thirty-nine percent of the procedures were performed for stable angina and 61% of the procedures for ACS. At the time of index PCI, 2.1% of patients had cardiogenic shock. Median follow-up was 700 days (interquartile range 341-1,122 days). The demographic, clinical and angiographic characteristics of all the patients are described in Table 1.

INCIDENCE OF STENT THROMBOSIS

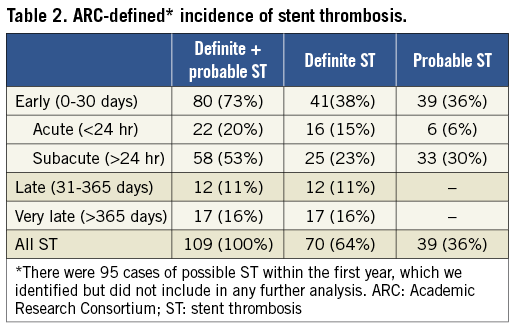

One hundred and nine patients (1.9%) had ST (70 definite, 39 probable). The subdivision of ST cases into the ARC-defined categories is given in Table 2. All cases of definite ST were based upon angiographic data, except for one case diagnosed at necropsy; 80% of them presented as acute MI and 20% as unstable angina. Sixty percent of cases of probable ST presented as deaths, 27% as acute MI, and 13% as unstable angina. There were 95 cases of possible ST during the first year of follow-up, all based upon deaths. The overall mortality during the study period was 6.1%; patients developing ST had substantially higher mortality (48.6% vs. 5.3%, p<0.001).

RISK FACTORS FOR STENT THROMBOSIS

At univariate analysis, cardiogenic shock, presentation as STEMI, lack of DAPT, renal dysfunction, diabetes mellitus, extent of coronary artery disease, multivessel PCI, number and types of stent used, and stent size (length and diameter) were associated with ST. Age, gender, smoking status, and previous coronary artery bypass graft were not associated with risk of ST.

Cardiogenic shock was strongly associated with ST. Of 112 patients with cardiogenic shock at the time of the index procedure, 10% (n=11) developed definite ST, whereas another 10% (n=11) developed probable ST. Eighteen of these 22 cases of ST (82%) occurred early (within 30 days). Patients presenting with cardiogenic shock were older (66±13 years vs. 63±11 years, p=0.013), often presented with STEMI (65% vs. 24%, p<0.001), had co-existing heart failure (23% vs. 1.5%, p<0.001), renal dysfunction (9% vs. 2%, p<0.001), and multivessel disease (1.9±0.9 vessels vs. 1.6±0.7 vessels, p<0.001). Gender, diabetes mellitus, and smoking status were not associated with cardiogenic shock (data not shown).

Ninety-three percent of patients were prescribed dual antiplatelet therapy (DAPT) which, in the majority of cases, consisted of aspirin and clopidogrel; only 6% of these (the cohort with ACS in 2010) received aspirin and prasugrel. The remaining 7% patients, who did not receive DAPT, received aspirin (3.5%), ticlopidine (1.4%), clopidogrel (2%), and warfarin (0.1%) for variable periods. Aspirin intolerance, bleeding problems or concomitant anticoagulation with warfarin were the commonest reasons for not prescribing DAPT. ST rates varied according to antiplatelet treatment. Warfarin treatment alone was associated with a 33% risk of ST. Patients not receiving DAPT had a higher incidence of ST than those on DAPT (6.7% vs. 1.5%, p<0.001).

The mean number of stents deployed per patient was 1.6. Forty-nine percent of stents were BMS and 51% were DES. Sixty-two percent of patients received a DES (some of them having a combination of BMS and DES) and 38% of patients received only a BMS. The DES used included those eluting sirolimus (11.1%), paclitaxel (25.7%), zotarolimus (26.3%), everolimus (34.6%), and biolimus (2.2%). There was no difference in the overall incidence of ST according to the use of BMS or DES (1.7% vs. 2.0%, p=0.69); however, first-generation DES (CYPHER®; Cordis, Johnson & Johnson, Warren, NJ, USA, and TAXUS®; Boston Scientific, Natick, MA, USA) tended to have more ST than newer DES (2.9% vs. 1.5%, p=0.013).

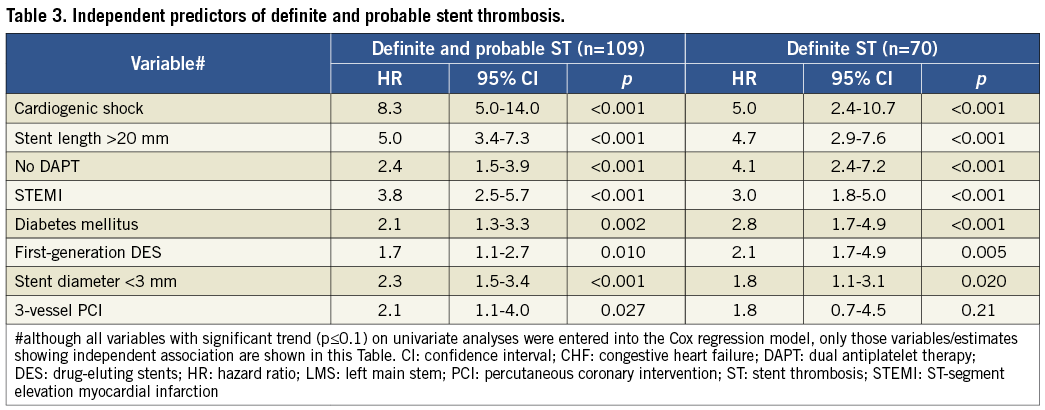

INDEPENDENT PREDICTORS OF DEFINITE AND PROBABLE ST

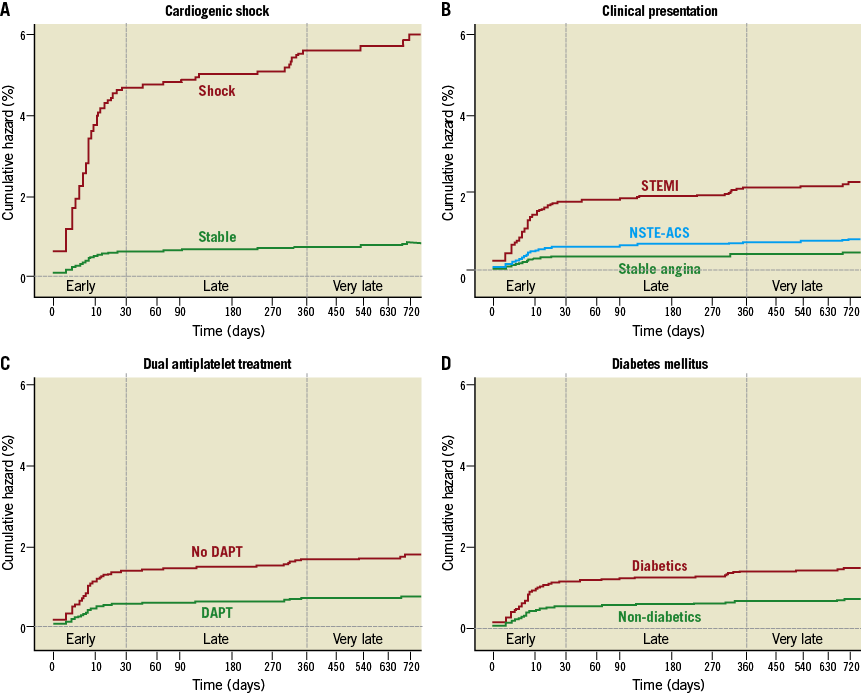

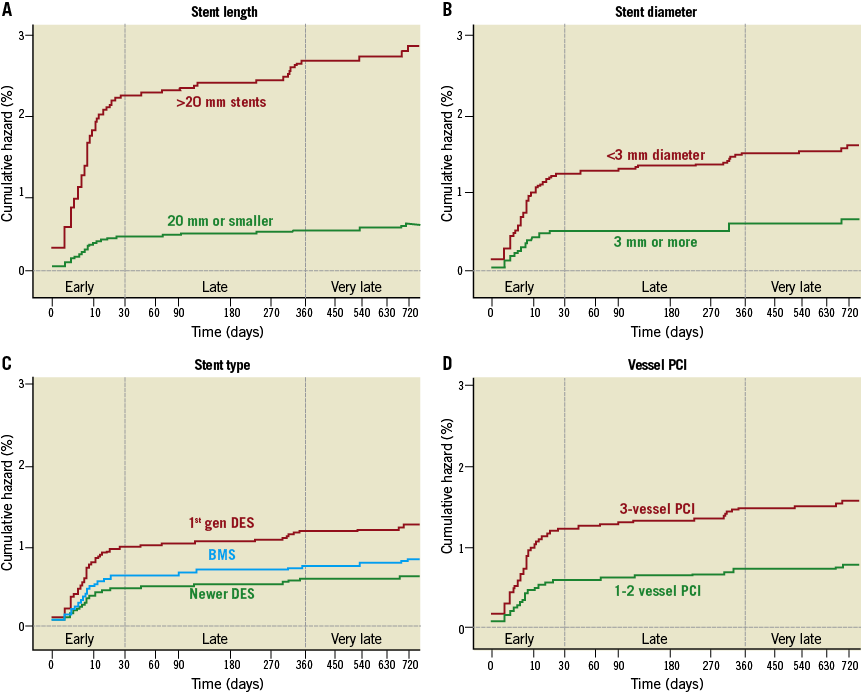

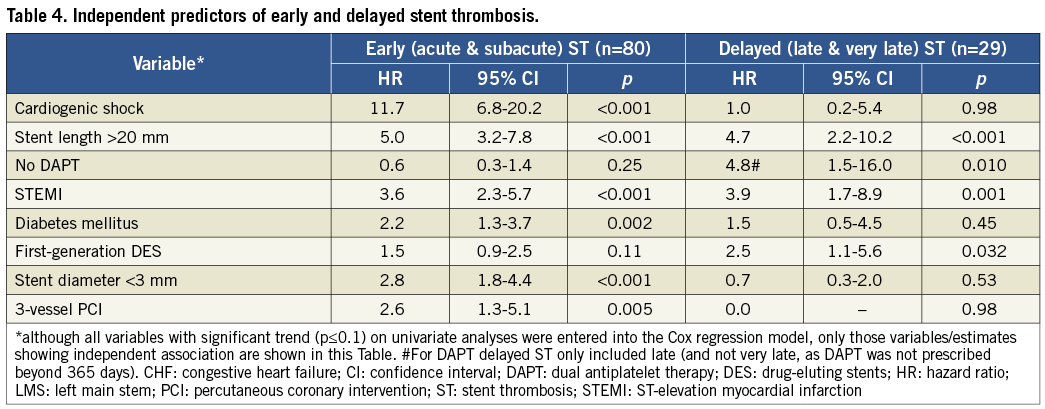

At multivariate analysis, some patient-related factors (cardiogenic shock, clinical presentation, lack of DAPT and diabetes mellitus [Figure 1]) and procedure-related factors (stent length, stent diameter, type of stent and 3-vessel PCI [Figure 2]) were independently associated with definite and probable ST (Table 3). All these factors, except 3-vessel PCI, were also independently associated with definite ST alone (Table 3). Analysis of definite and probable ST together revealed that cardiogenic shock, stent size (small diameter and long length), STEMI, diabetes mellitus, and 3-vessel PCI were also associated with early (acute and subacute) ST (Table 4). Lack of DAPT was associated with late ST (Table 4). Stent length, STEMI, and use of first-generation DES were independently associated with delayed (late and very late) ST (Table 4).

Figure 1. Patient-related factors associated with stent thrombosis. Kaplan-Meier curves showing adjusted association of stent thrombosis with cardiogenic shock (A), clinical presentation (B), dual antiplatelet treatment (C), and diabetes mellitus (D).

Figure 2. Procedure-related factors associated with stent thrombosis. Kaplan-Meier curves showing adjusted association of stent thrombosis with stent length (A), stent diameter (B), stent type (C), and 3-vessel PCI (D).

Discussion

In this “real-world” registry of 5,833 “all-comer” patients undergoing PCI, we found a 1.9% incidence of definite/probable ST (definite 1.2%, probable 0.7%). These figures are similar to other contemporary registries: 1.2% definite ST seen in the Swedish Coronary Angiography and Angioplasty Registry (SCAAR)10 and 1.3% definite ST in the Spanish Registry (ESTROFA)14. Our incidence of 1.9% definite plus probable ST is also comparable with recent trials: for example, 1.7% ST for zotarolimus-eluting stents20 and 2.6% for biolimus-eluting stents21. However, the trials with everolimus-eluting stents have generally reported a lower (<1%) incidence of ST20,22.

Cardiogenic shock emerged as the strongest predictor of ST (both definite and definite/probable) in our study. This has not been previously reported, because these very high-risk patients are commonly excluded from trials (including the landmark TRITON-TIMI 38 and PLATO trials)23,24, and are under-represented even in registries (often only reported in “real-world, all-comer” studies and case reports)25,26. Age, heart failure and renal dysfunction, although in our study not independent risk factors for ST, were strongly associated with cardiogenic shock at presentation. The presence of cardiogenic shock could have important implications for the choice of antiplatelet therapy and revascularisation strategy. The bioavailability of thienopyridine type antiplatelet agents (clopidogrel and prasugrel), which are inactive pro-drugs and require conversion to active drugs, may be reduced in cardiogenic shock26,27. The non-thienopyridine oral P2Y12 inhibitor ticagrelor does not require metabolic conversion to achieve its antiplatelet activity but, like prasugrel, may have delayed onset of action in STEMI patients28 presumably related to delayed absorption. In order to circumvent this problem, intravenous antiplatelet therapy (such as cangrelor or abciximab) may have a role in these patients23,29,30. STEMI patients were at a significant risk of developing early ST, consistent with previously published data5. It is generally advocated that STEMI patients presenting with cardiogenic shock should have complete (as opposed to culprit-only) revascularisation31. However, our results highlighting a very high incidence of ST in this cohort provide a note of caution. It is notable that, in the SHOCK trial, multivessel PCI independently correlated with mortality32. The 2012 ESC guidelines suggest that “non-culprit” lesion PCI in STEMI patients with shock should only be for “truly critical (≥90% diameter) stenosis or highly unstable lesions (angiographic signs of possible thrombus or lesion disruption), and if there is persistent ischaemia after PCI of the supposed culprit lesion”33.

Other risk factors for definite ST included lack of DAPT, presentation with a STEMI, stent size (length and diameter), and diabetes mellitus. Lack or discontinuation of DAPT is a well-documented risk factor for ST in all studies5,10 and our study also confirmed this. A very small proportion (0.1%) of patients received warfarin only, and unsurprisingly had a very high (33%) incidence of ST. It remains unclear whether this could be due to associated comorbidities, lack of DAPT, or a prothrombotic effect of warfarin itself. Although the numbers are too small to draw any conclusion, this finding is consistent with the results seen in the SCAAR registry10. ESC guidelines recommend DAPT for one month in patients taking warfarin who undergo PCI, unless there is a contraindication or a substantial risk of bleeding. The recently presented WOEST trial suggests that warfarin combined with clopidogrel could be a potential option in such patients34. In our study, use of first-generation DES was an independent predictor of late and very late ST, consistent with previous reports18,35. Stent size, particularly stent length, is an important determinant of ST in previous studies10,14, and our study also confirmed these findings.

Study limitations

This is an observational study, with the data derived from a prospectively compiled register and retrospectively from patient records. In addition, some aspects of the data were unconfirmed: for example, we did not evaluate patients’ compliance with their antiplatelet treatment and our results are based on antiplatelet prescription only. Finally, although outcome data are complete for mortality, the chance of missing a non-fatal event in a patient who presented elsewhere cannot be excluded. However, using “all-comers” data for a large number of patients, we identified risk factors for stent thrombosis, which could help clinicians to take extra measures to prevent this serious complication.

Conclusion

This study examined the incidence of ST in a “real-world” practice and identified high-risk patients to whom special attention should be paid regarding procedural practice and selection of stents and antiplatelet agents, in an attempt to minimise the risk of ST.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to all the interventional cardiologists at South Yorkshire Cardiothoracic Centre. We would also like to thank Louisa Yates and Marzena Whittaker for help in data extraction and Naila Sarwer for statistical support.

Conflict of interest statement

R.F. Storey declares consultancy, honoraria and/or institutional grants from AstraZeneca, Eli Lilly, Daiichi Sankyo, Accumetrics, Merck, Novartis, Eiasi, Iroko, The Medicines Company, Sanofi Aventis and Bristol Myers Squibb. The other authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.